Competition seeks to revive Tripoli’s fair

A version of this article appeared in the web edition of The Daily Star on July 13, 2019.

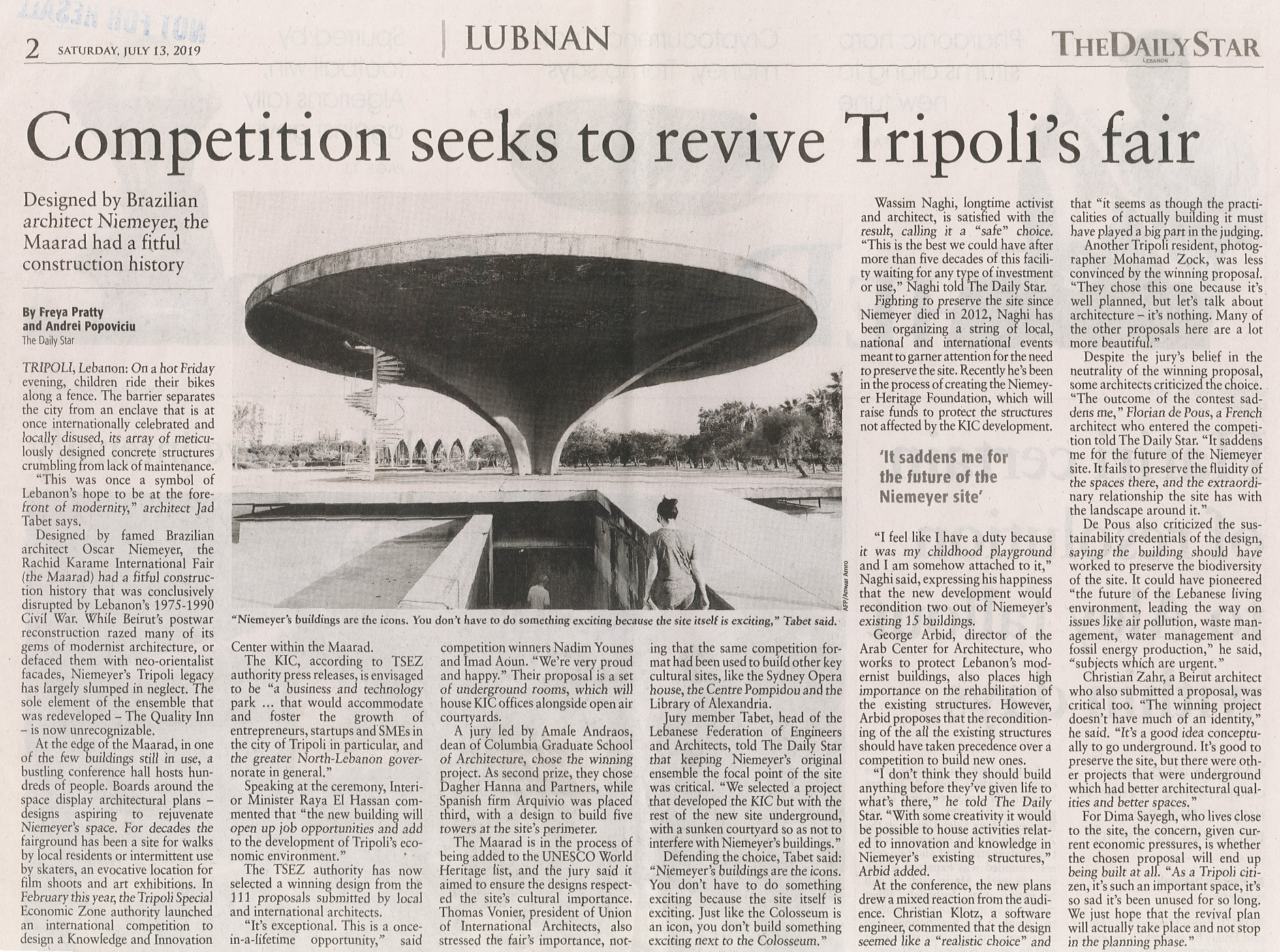

TRIPOLI, Lebanon: On a hot Friday evening, children ride their bikes along a fence. The barrier separates the city from an enclave that is at once internationally celebrated and locally disused, its array of meticulously designed concrete structures crumbling from lack of maintenance. “This was once a symbol of Lebanon’s hope to be at the forefront of modernity,” architect Jad Tabet says.

Designed by famed Brazilian architect Oscar Niemeyer, the Rachid Karame International Fair (the Maarad) had a fitful construction history that was conclusively disrupted by Lebanon’s 1975-1990 Civil War. While Beirut’s postwar reconstruction razed many of its gems of modernist architecture, or defaced them with neo-orientalist facades, Niemeyer’s Tripoli legacy has largely slumped in neglect. The sole element of the ensemble that was redeveloped - The Quality Inn - is now unrecognizable.

At the edge of the Maarad, in one of the few buildings still in use, a bustling conference hall hosts hundreds of people. Boards around the space display architectural plans - designs aspiring to rejuvenate Niemeyer’s space. For decades the fairground has been a site for walks by local residents or intermittent use by skaters, an evocative location for film shoots and art exhibitions. In February this year, the Tripoli Special Economic Zone authority launched an international competition to design a Knowledge and Innovation Center within the Maarad.

The KIC, according to TSEZ authority press releases, is envisaged to be “a business and technology park ... that would accommodate and foster the growth of entrepreneurs, startups and SMEs in the city of Tripoli in particular, and the greater North-Lebanon governorate in general.”

Speaking at the ceremony, Interior Minister Raya El Hassan commented that “the new building will open up job opportunities and add to the development of Tripoli’s economic environment.”

The TSEZ authority has now selected a winning design from the 111 proposals submitted by local and international architects.

“It’s exceptional. This is a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity,” said competition winners Nadim Younes and Imad Aoun. “We’re very proud and happy.” Their proposal is a set of underground rooms, which will house KIC offices alongside open air courtyards.

A jury led by Amale Andraos, dean of Columbia Graduate School of Architecture, chose the winning project. As second prize, they chose Dagher Hanna and Partners, while Spanish firm Arquivio was placed third, with a design to build five towers at the site’s perimeter.

The Maarad is in the process of being added to the UNESCO World Heritage list, and the jury said it aimed to ensure the designs respected the site’s cultural importance. Thomas Vonier, president of Union of International Architects, also stressed the fair’s importance, noting that the same competition format had been used to build other key cultural sites, like the Sydney Opera house, the Centre Pompidou and the Library of Alexandria.

Jury member Tabet, head of the Lebanese Federation of Engineers and Architects, told The Daily Star that keeping Niemeyer’s original ensemble the focal point of the site was critical. “We selected a project that developed the KIC but with the rest of the new site underground, with a sunken courtyard so as not to interfere with Niemeyer’s buildings.”

Defending the choice, Tabet said: “Niemeyer’s buildings are the icons. You don’t have to do something exciting because the site itself is exciting. Just like the Colosseum is an icon, you don’t build something exciting next to the Colosseum.”

Wassim Naghi, longtime activist and architect, is satisfied with the result, calling it a “safe” choice. “This is the best we could have after more than five decades of this facility waiting for any type of investment or use,” Naghi told The Daily Star.

Fighting to preserve the site since Niemeyer died in 2012, Naghi has been organizing a string of local, national and international events meant to garner attention for the need to preserve the site. Recently he’s been in the process of creating the Niemeyer Heritage Foundation, which will raise funds to protect the structures not affected by the KIC development.

“I feel like I have a duty because it was my childhood playground and I am somehow attached to it,” Naghi said, expressing his happiness that the new development would recondition two out of Niemeyer’s existing 15 buildings.

George Arbid, director of the Arab Center for Architecture, who works to protect Lebanon’s modernist buildings, also places high importance on the rehabilitation of the existing structures. However, Arbid proposes that the reconditioning of the all the existing structures should have taken precedence over a competition to build new ones.

“I don’t think they should build anything before they’ve given life to what’s there,” he told The Daily Star. “With some creativity it would be possible to house activities related to innovation and knowledge in Niemeyer’s existing structures,” Arbid added.

At the conference, the new plans drew a mixed reaction from the audience. Christian Klotz, a software engineer, commented that the design seemed like a “realistic choice” and that “it seems as though the practicalities of actually building it must have played a big part in the judging.

Another Tripoli resident, photographer Mohamad Zock, was less convinced by the winning proposal. “They chose this one because it’s well planned, but let’s talk about architecture - it’s nothing. Many of the other proposals here are a lot more beautiful.”

Despite the jury’s belief in the neutrality of the winning proposal, some architects criticized the choice. “The outcome of the contest saddens me,” Florian de Pous, a French architect who entered the competition told The Daily Star. “It saddens me for the future of the Niemeyer site. It fails to preserve the fluidity of the spaces there, and the extraordinary relationship the site has with the landscape around it.”

De Pous also criticized the sustainability credentials of the design, saying the building should have worked to preserve the biodiversity of the site. It could have pioneered “the future of the Lebanese living environment, leading the way on issues like air pollution, waste management, water management and fossil energy production,” he said, “subjects which are urgent.”

Christian Zahr, a Beirut architect who also submitted a proposal, was critical too. “The winning project doesn’t have much of an identity,” he said. “It’s a good idea conceptually to go underground. It’s good to preserve the site, but there were other projects that were underground which had better architectural qualities and better spaces.”

For Dima Sayegh, who lives close to the site, the concern, given current economic pressures, is whether the chosen proposal will end up being built at all. “As a Tripoli citizen, it’s such an important space, it’s so sad it’s been unused for so long. We just hope that the revival plan will actually take place and not stop in the planning phase.”

Post a comment